Starship Tweedy

Written by David Kushner, Disruptor

Thursday October 21st, 2021

I spoke with Wilco's Jeff Tweedy about his new newsletter, Starship Casual, losing his parents, and how his stage persona almost destroyed him. "It turned into things that were killing me," he says.

Jeff Tweedy is a busy man, even during a pandemic. In the last year, the 54-year-old singer and songwriter for Wilco has published his second book, livestreamed an Instagram series, embarked on a concert tour, and put out a new solo record (including a deluxe edition he announced this week). As if that’s not enough, he’s also now sharing memories, songs, and perhaps some parenting advice in his new Substack newsletter, Starship Casual. I caught up with Tweedy earlier this month when he was on the road with Wilco in Portland.

David Kushner: What interested you in starting Starship Casual ?

Jeff Tweedy: I’d seen Substack and links to Substack on Twitter and stuff like that, but I wasn’t really totally up to speed on what it was. Once I started looking at it, I started having all kinds of ideas about how you could use it. It’s like getting to put out my own little mini-magazine publication devoted to just whatever I’m feeling.

David Kushner: In your intro post to Starship Casual, you refer to insights you’ve gained from trying to make social media feel worthwhile and honest. What insights are those?

Jeff Tweedy: Well, George [Saunders, the novelist] had a really fantastic phrase describing Substack to me as like social media purified by conscience. One of the things that is conscienceless about a lot of other forms of social media is mitigating your desire for attention with just how tempting it is to engage in a daily economy of outrage. Everything that you do that’s outward-facing to the public is curated to some degree, you can’t really avoid that. But I think it’s really interesting trying to curate really small little fragments in other forms of social media too. I honestly don’t quite get the point sometimes. I think it’s reaching outwards for some connection. I don’t find that to be particularly troublesome, but I’m not sure that I’ve completely figured it out. I just know that it wasn’t for me. I might have said I have some insights, but insights are kind of overrated. It’s just more of a feeling that I didn’t trust when I’ve dabbled in it. I didn’t really trust the way that I wanted to portray myself.

“Everybody wants to feel like they could hang out with their favorite singer.”

David Kushner: During the pandemic, you started streaming The Tweedy Show with your family in your house. How did that experience open you up to sharing even more in Starship Casual?

Jeff Tweedy: The Tweedy Show was really my wife’s idea to do it on her Instagram and keep it a little bit separate from the Wilco official sites or my own Instagram, and just try and allow it to be something that organically grows. We really wanted to acknowledge and pay respect to the notion that everybody in the world conceivably was going through a similar experience for the first time in any of our lives. There were no stages. There was no hierarchy of whose entertainment is more valued over someone else’s. It’s all available to everyone, based on the technology available to them. I found that to be really liberating. I’ve always wanted to feel that way about the musicians and the performers and the people that I am drawn to. Everybody wants to feel like they could hang out with their favorite singer.

David Kushner: What is about this way of reaching your audience that appeals to you?

Jeff Tweedy: On the internet, there’s more immediate responses to things. But it doesn’t ever really feel like people come at it acknowledging the spirit of how it was made. They come at it like, ‘oh, this is a Wilco record. I need to put it into context.’ There’s just baggage with everything. I always have craved that feeling of playing a song for someone or saying something to someone, and then feeling that immediate give and take. You only really get that one on one. Early on when I first started writing songs, I’d play them for my mom. She wouldn’t necessarily get them, but she would receive them in the spirit that they were created. Like, I’m not trying to do anything wrong. I’m not trying to get one over on anybody. I’m not trying to assert my intellect as superior or anything. But people get all kinds of mixed reactions to how you put things into the world, especially when you put a price tag on it, like ‘who does he think he is? This is worth a lot? You know, you think this is worth this?’

I started doing this with friends on text, sending them a song a day. And I do it with Wilco now. It’s like the only place I really get this kind of genuine, in-the-moment, ‘wow, thank you for playing that song for me.’ It’s not like I need to hear ‘that’s the greatest song I’ve ever heard in my life.’ It’s like, ‘oh, you shared your song with me, I really feel like special because you shared your song with me, thank you.’ It’s really simple and direct. The Tweedy Show was like that too. That was an initial foray into realizing that that’s available through technology in a way that I never had explored.

David Kushner: I think some people would find that surprising, because you’re up there sharing your songs every night. You have been doing it for decades with an audience who are receptive and responding.

Jeff Tweedy: An audience is a thing that doesn’t really have a centralized consciousness. So it’s kind of unwieldy and it’s hard. My natural, evolutionarily-derived instinct is to find the people that aren’t enjoying themselves in an audience, sensing danger, like, ‘what’s this guy yawning about?’ They could be surrounded by people dancing, and you’ll pick them out. It’s just like being on the Savannah, and looking for the tiger. I feel like gazelle.

David Kushner: The first song that you shared in Starship Casual, “A Lifetime to Find,” is a ballad about death. Why start with that one?

Jeff Tweedy: It was just a song. It just popped into my head and. I didn’t really spend a whole lot of time looking for something. I just like went through my phone and I listened to that one and I thought, ‘oh, I’d like to see what people think of that.’ It’s also probably because I’ve written a lot for the next Wilco record. And I have a lot of songs like that I don’t see fitting into the Wilco record the way it stands. The Wilco record that we’re working on is in a different direction, sonically. That one is sort of a folk tradition type song, and I write lots of those. I think part of me was saying, ‘God, if you don’t share it here, who knows how long it’ll be before you get a chance?’

“I went from writing about a morbid set of fears to writing about a morbid set of realities.”

David Kushner: Part of what you’ve been sharing – in your memoir, and in recent songs like “Orphan” – is your experience of losing your parents. How has that loss shaped you as an artist and opened you up to sharing more with your audience?

Jeff Tweedy: My mom dying was probably my worst fear my whole life. Living through that would’ve been the first transition to actually having experienced the worst-case scenario, as far as your deepest fears about how you’re going to cope with the world and live through it. It was pretty obvious early on that I wasn’t dying too. That doesn’t take any of the sadness or the grief away, but it is kind of amazing how quickly you realize that, okay, that’s the worst thing I could have ever imagined. And I’m still here. I’m still I’m able to think, even though I completely lost my mind.

With my dad dying, I wouldn’t have expected it to be so profound because it was a difficult relationship a lot of my life. I wouldn’t have ever described myself as being particularly close to my father. But I realized as he was dying, and in the few years before preceding his death, how similar we are. I diagnosed him late in life with a lot of the same mood disorders that I like have to contend with. And I think he was difficult probably because he’s self-medicated for a lot of the same things. I’ve been able to find better help. I do think that there’s some transition there. It was going from writing about a morbid set of fears to writing about a morbid set of realities.

David Kushner: Do you think your posts in Starship Casual as forming a larger narrative about you and your life?

Jeff Tweedy: Yeah, I think so. It’s a little too early to tell. I think if it really does form something coherent, I think it will. I’m really wanting to normalize shorter paragraphs. I think a lot of storytelling and a lot of the way people write is rooted in this idea that you need to get everybody to see everything in the room and qualify everything. I’m just not really good at writing like that. I like haiku. I like poems. I’m trying to get to the essence of memory. It doesn’t even have to be accurate, because I think that there’s really beauty in the way you tell a story that doesn’t require a lot of those specifics.

David Kushner: Between your two books and your newsletter, you’ve had to transition from songwriting to prose. What are the challenges in that for you?

Jeff Tweedy: With the first book, I felt like I could do it, but I didn’t feel like I was going to enjoy it. Because it was hard and it was so different. it’s like the photo negative of what I try and get at with a song. It’s like putting all of the things in there that I try and cut away from a song. Especially in a memoir, you’re trying to make it as clear as possible. With my songs, I’ve tried to make as much room for the listener as possible, to have space for them to color in. But once I got going, honestly, it started to feel really good. It was an incredible sense of accomplishment having finished it. I’ve heard other writers say that ‘I hate writing, but I love finishing a book.’ That’s a really, really, really good feeling. And the second book, I think I was just in the zone for that book. It was early in the pandemic. I was home with the family, but spending a lot of time in solitude thinking about the thing that I think about the most and trying to share my thoughts about creativity. It’s not necessarily about writing a song, but just being given a chance to be an advocate for creativity. That’s what I looked at it. Somebody gave me an opportunity to write a book that where I could tell people, ‘Hey, this is good for you. I don’t care if you’re good or not, you should do something.’”

David Kushner: Is that something you plan to do more in Starship Casual, write about songwriting and the creative process?

Jeff Tweedy: Yeah. I don’t know. I mean it could go in any direction at this point. The next thing on the agenda for expanding a little bit on the newsletter would be to incorporate some friendly advice, solicit some questions.

David Kushner: What kind of questions have people had for you?

Jeff Tweedy: Well the sincere questions, I think there were a lot of them about parenting, which is really How to Raise One Child. Maybe that’s the next book.

David Kushner: What’s your advice for the parenting people out there?

Jeff Tweedy: I’m a big advocate of good enough parenting. I think when you try and win at parenting, you’re almost inevitably going to do some damage.

David Kushner: With all this prose writing, what about fiction? Have you thought about writing short stories or a novel?

Jeff Tweedy: It’s been a really long time since I’ve been as interested in other people’s fiction. I love books. I’m a big reader. I’m still kind of catching up with the 20th century as far as fiction goes.

David Kushner: What’s on your nightstand or on your Kindle?

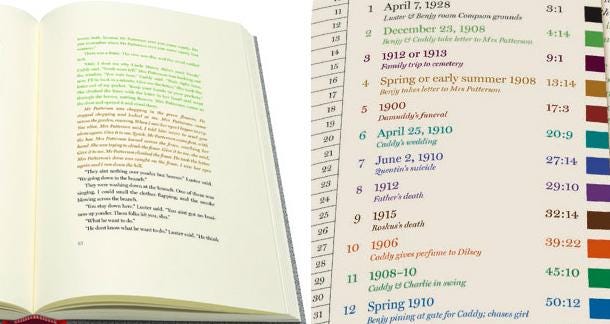

Jeff Tweedy: Well, it’s not on my Kindle, but it’s The Sound And The Fury. There’s an edition of it where they actually printed it the way that he had initially wanted it to be printed, where all of the different temporal jumps were written in different colored inks. In the narrative, there’s only a handful of days that they’re really talking about in the time frame. So whenever any character is talking about a specific date, it’s in a different colored ink, and there’s like a little guide with it. That was incredibly helpful. It was like a really difficult book to know who’s talking, get your head around. So that’s been fun. It has led me to kind of rereading the Snopes books.

David Kushner: What other authors have had a big impact on you would you say as a writer?

Jeff Tweedy: Well in the newsletter in particular, David Markson. I don’t think it would’ve ever occurred to me to write this way without being in love with his books. And in particular, his four books that are written using notecards. I think he never wrote a paragraph that was longer than he could fit on a notecard. And then he would just organize them into these narratives. One book is called Reader’s Block and there’s This is Not a Novel. It’s very similar to the way that my memories work. But he’s incorporating just fragments of his knowledge of other artists or other people, other composers’ lives and authors’ lives. A typical sentence in a David Markson book would be like, ‘Celine was an anti-Semite.’ It’s mesmerizing reading those books, because there’s such short, concise pieces of language. His use of grammar is so powerful because the syntax of how he constructs these sentences ends up having this rhythm to it. I feel like I walk away from reading a David Markson book for an hour or so thinking in those types of sentences.

David Kushner: The Rememories you’re writing in the newsletter are interesting in that way, because they does seem a stream of consciousness, like you’re starting with one memory and just kind of seeing where it goes. Is that an exercise for you?

Jeff Tweedy: They are written like that. I’ll just think what’s a story that I tell about my life to my friends or to my kids. I’ll just start with like, ‘oh, how can I get that story down without boring someone?’ Sometimes it takes a few paragraphs to get to the punchline of the story or the takeaway from the story. Sometimes it’s really quick. But as I’m writing one, it usually does pop some other memory into my head and I try and honor that and write them as they come.

David Kushner: Is your desire to write in a more concise, encapsulated way because of the medium here? You’re writing something that’s landing in someone’s email inbox.

Jeff Tweedy: Well, I think it’s a really satisfying way of writing for me. I really enjoy it. I find it to be really evocative and challenging to get language to be that emotive and at the same time being so sparse or kind of streamlined. I think it’s just a coincidence that it’s something I really wanted to do. Then it is something that kind of lends itself really well to the way people consume a newsletter or a lot of things in their inbox or the way that people consume information all day long even. It just seems like a natural way to communicate. I think it’s really daunting for somebody sitting in the morning, opening up all their emails to see big paragraphs of information.

I think you can skim the types of paragraphs I’m writing, hopefully without even reading them and get the gist of where things are going. That’s the way I think memory works. If I could transfer my memory to someone else, I think the keywords are really all that’s going to stick with you. I think if you can get the keywords to jump out that memory is going to form probably similar to mine. It might not be exactly the same, but it will have a similar resonance.

“Nobody is constructing a version of me that’s accurate, no matter how much I share.”

David Kushner: In How to Write One Song, you wrote about using the cut-up technique, which reminds me of what William S. Burroughs did. How does writing like this enable you to get to a different sort of truth?

Jeff Tweedy: I think a lot of artists have trouble being an authority on things like truth. I want to be kind and emotionally open and available and connected, and I don’t want to be a liar and I don’t want to be false. But when it comes to my experience of the world and relating that experience of the world to someone else, the last thing I would want is for somebody to think that I’m less fallible than they are somehow in expressing that.

David Kushner: With all this writing, do you every worry about oversharing?

Jeff Tweedy: Oh, I think everybody has so much inside of them. There’s things that I’m not aware of, that I haven’t gotten to for myself. We all carry around things that we haven’t unpacked. So I’m never worried about that. I guess overexposure is a thing or familiarity can breed some sort of contempt, but no. It’s like people ask me that about the book, too. Did you give away all your secrets? And I feel the same way about this. Nobody is actually constructing a version of me that’s accurate, no matter how much I share. No one would take all of the different things that I use to write a song and write a song that sounds like one of mine exactly, if they’re doing it right. I think you could go and imitate someone else’s style, but that’s not what my book is describing. Those aren’t the steps or that’s not the process you would use to write, “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart.” It’s just the process that was used to write, “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart.” Now when I used it again, it wrote something else. And when I used it the next time it wrote something else. It works that way for me, I would assume it would work even more so for someone else.

David Kushner: What else do you have planned for Starship Casual in the future?

Jeff Tweedy: Well, there’s the advice stuff. One thing that I get asked about a lot is gear, musical gear and stuff like that. I love it and I find it interesting. I’m kind of going back and forth on whether or not there’s a place for it on Starship Casual. I think that there are emotional stories I can tell, or ways to share that information that doesn’t feel just like gear talk but I’m still wrestling with it

David Kushner: What was the idea behind calling this Starship Casual?

Jeff Tweedy: Starship Casual, that whole idea to me was that we walk around using these devices that have the computing power of whatever, beyond what it took to go to the moon. But we’re not trying to discover new worlds or anything, we’re just trying to connect in a way. And I think that’s a pretty amazing use of this almost hard-to-believe equipment we carry around.

“I realized, ‘oh, you don’t have to fucking do that. You’re good enough just being. These people are on your side.’”

David Kushner: Well, it’s all so new too. I mean, you and Patti Smith are some of the first artists to start doing this. It’ll be interesting to see how it evolves.

Jeff Tweedy: Yeah. I’m interested. I’m cut out for it, because one of the things that was really hard for me early on was the idea that I had to have a different personality or a different persona on stage than who I was. That was something that never came naturally to me, and it was really disorienting or early on. It made it really hard going on the road and coming home to my kids and stuff like that. And at some point I figured out I’m going to spend every second of my life trying to make those two people feel compatible with each other because it was painful and it caused me damage and it made it hard to get better. It turned into things that were killing me. Then I figured out, ‘oh, you can be the same fucking person!’” Jonathan Richmond is the same fucking person, he’s my hero. Patti Smith for all of her, for all of her artifice and grandiosity, she is that person I’ve met her. She thinks and acts that way. So it was just a revelation: ‘oh, that’s cool, that’s being an outward advocate for just being your own fucking person.’

David Kushner: How did you end up reconciling those two parts of yourself?

Jeff Tweedy: I don’t really know. I think it might have just been a switch. It might have just been, like when I realized, ‘oh, you don’t have to fucking do that. You’re good enough just being. These people are on your side. They didn’t come here to see you try and be Joe Strummer or something. They didn’t pay to see the glamour. You’re not glamorous Jeff Tweedy.